The Long Shadow of the Columbus Police Vice Unit

Four years since the disbandment of a corrupt police unit, Columbus continues to feel the aftershocks of the scandal. This is the story of how the squad went astray, plus a look at what replaced it.

Ed Hastie’s wife woke him suddenly in the early morning hours of July 12, 2018, relaying the news that adult film star Stormy Daniels had been arrested at Sirens, a Northeast Columbus strip club that Hastie represents in his law practice. “She’s almost slapping me, like, ‘You dumb bastard. You should have gone to the strip club last night!’” Hastie says. “I don’t know any man who’s been told that by his wife.”

Before going to bed the night before, Hastie traded benign text messages with Sirens manager Jay Nelson, who informed the attorney that things were running smoothly. The crowds were large and mostly well-behaved. And Daniels (whose real name is Stephanie Clifford) treated staff members with kindness, showing little effect from the intense national spotlight that landed on her after she broke the news that President Donald Trump made hush payments to her prior to his presidential run in 2016.

Hastie fished for his phone, which he had tucked under his pillow. When he powered it on, he says it lit up with so many text messages that the figure displayed not as a number but a collection of symbols. He started replying, eventually connecting again with Nelson, who told him that Columbus police had arrested three women, including Daniels.

The raid was odd on multiple levels. Sirens didn’t have a history of criminal activity and hadn’t received complaints from neighbors. What’s more, the investigators – a ragtag group from CPD’s Vice Unit – didn’t act like inconspicuous, undercover officers. They behaved belligerently, threw money around freely and were among the first to visit with Daniels when she moved to the VIP section. During the adult film star’s time onstage, the group watched her press her breasts against the faces of numerous customers, arresting her after she made contact with the officers. Also arrested were two Sirens employees, Miranda Panda and Brittany Walters.

After his phone call with Nelson, Hastie dialed Steven Rosser, a CPD veteran the lawyer had gotten to know litigating liquor law. Over a half decade in Columbus vice, Rosser had earned a reputation for secrecy, boldness and independence. When Hastie got the detective on the phone, Rosser remained tight-lipped. “You and I probably shouldn’t talk about this,” he said.

While Rosser brushed off Hastie’s inquiry on that summer day nearly five years ago, the detective couldn’t stop all the forces that his bizarre, ill-fated raid had unleashed – an overdue reckoning that continues to resonate today. The day after the raid, Columbus City Attorney Zach Klein dropped all charges against Daniels, and a week later he did the same for Panda and Walters. Klein’s office determined the misdemeanor counts filed against them by police were a misguided use of Ohio’s Community Defense Act, which prohibits those who work in sexually oriented businesses from touching people to whom they are unrelated. Daniels was charged even though the law requires the suspect to be a regular performer (she wasn’t) and the recipient to be a patron, which Klein defined as someone not operating in an official capacity (the officers were). Meanwhile, Panda, who was fully clothed, was charged after she smacked the buttocks of another clothed female co-worker in response to a crude comment from one of the undercover officers, says Hastie, who represented Panda and Walters. (Walters was accused of touching a patron.)

The cases seemed to confirm long-held concerns within Columbus police about the vice squad, whose personnel (which included 16 officers, three sergeants and a lieutenant) worked a specialized beat with little oversight amid lots of temptation. Even before the Daniels bust, then-Columbus police chief Kim Jacobs had begun to explore how to fix what she and others considered a troubled unit, says Jeff Furbee, CPD’s legal adviser, who’s worked for the Columbus City Attorney’s Office for nearly 20 years. “There were good people in vice, but as a unit, it drifted off course,” Furbee says. “Somebody at the top of the division at the time said, ‘The people we want to be in vice aren’t the people who want to be in vice, and the people who want to be in vice aren’t the people we want.’”

Indeed, a troubling culture emerged as police brass and others began to look closer at vice. In September 2019, Jacobs paused the unit and requested investigative help from the FBI’s Public Corruption Task Force. Six months later, Columbus police announced the dissolution of vice in the wake of the external and internal probes. Anna Harvey, a professor of politics and director of the Public Safety Lab at New York University, says part of the issue can be traced back to vice units’ emphasis on undercover work rather than maintaining a highly visible, uniformed police presence, which research has shown is the most effective form of crime deterrence. “Specialized units like the Columbus Vice Unit are, by construction, not visible,” Harvey says. “So they, by definition, have no deterrence. All they have are arrests. … And we know that arrests are a terrible measure of safety.”

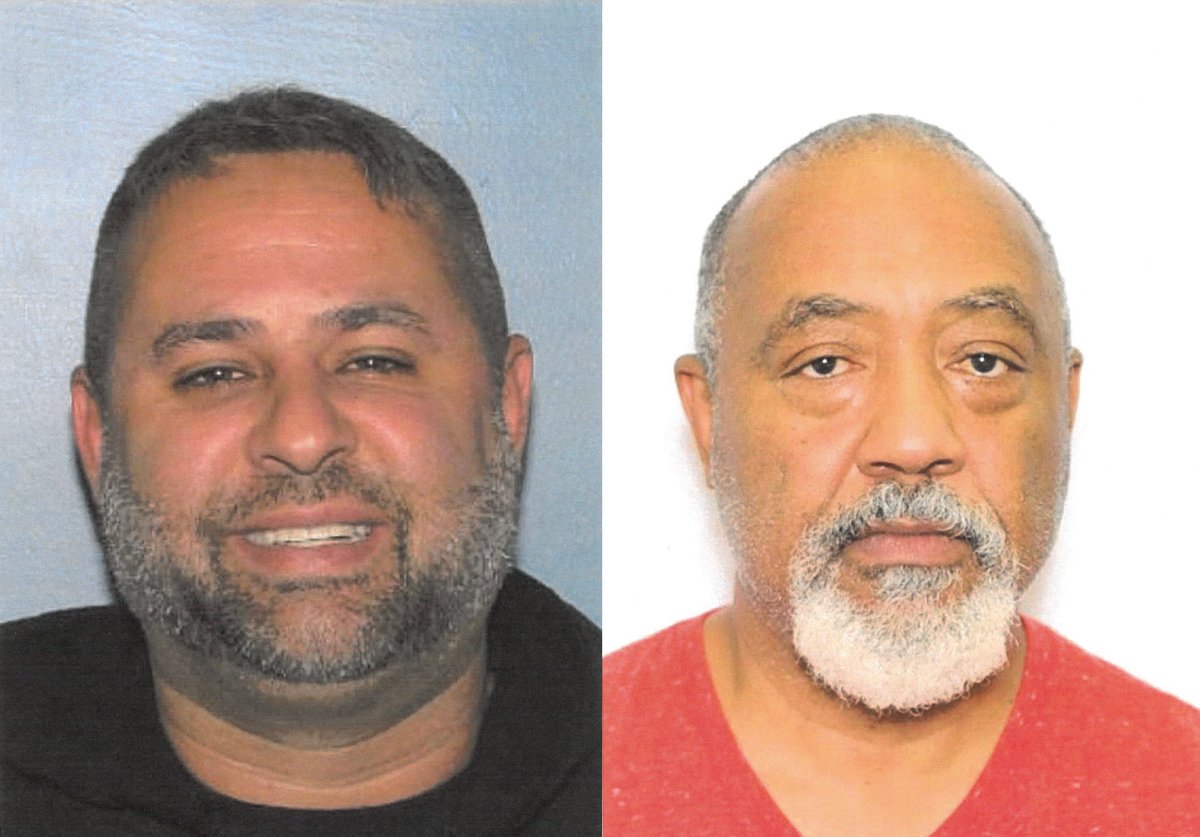

In Columbus, the most high-profile misconduct allegations have focused on vice officer Andrew Mitchell, who shot and killed 23-year-old Donna Dalton Castleberry in plainclothes after trapping her in his vehicle in August 2018, just over a month after the Daniels raid. A mistrial was declared in his first trial on murder and voluntary manslaughter charges last spring, and in April a Franklin County jury found him not guilty. In July, Mitchell will face a third trial – this time in U.S. District Court in Columbus on nine federal charges stemming from accusations by two women who allege he kidnapped them and forced them to perform sex acts in exchange for their freedom.

Though the Mitchell saga has attracted the most publicity, the story of Steven Rosser deserves attention, too. Now serving an 18-month federal prison sentence for conspiring to violate the civil rights of a strip club owner, Rosser, the architect of the Daniels bust, “wants to put this chapter behind him and isn’t interested in being interviewed,” says his attorney, Steven Nolder. But others involved in the story were willing to talk, including many sources who spoke publicly for the first time. These interviews – and a voluminous legal paper trail – reveal a rot that grew from within the city police department: lies, violence, impunity, intimidation, corruption. It’s a squalid affair that offers critical lessons for CPD leaders. With top brass creating other specialized units similar to vice, they risk repeating the mistakes of the recent past if they ignore the long shadow of this law enforcement failure.

The rules didn’t always apply to Rosser. While the vice squad guidelines permitted drinking alcoholic beverages during official investigations, officers weren’t allowed to reach the point of impairment, unless exceptions were approved in advance. In interviews and court documents, witnesses described Rosser frequently ignoring that standard.

Rosser also seemed intoxicated by the power of the badge. He used it to promise things he couldn’t deliver, like jobs on the police force. And he used it to punish people and businesses for reasons that often seemed personal. In 2014, only a year after joining the vice beat, Rosser stirred controversy at the Goat, a New Albany-area bar. Rosser ate and drank there, played on the tavern’s volleyball team and had a romantic relationship with a Goat bartender.

So imagine the Goat employees’ surprise when, some time after Rosser’s relationship with the bartender ended, he used confidential informants to cite several Goat workers for serving alcohol to minors. In 2015, Franklin County Municipal Court Judge David Tyack acquitted the employees of the charges, ruling that Rosser entrapped them. “Detective Rosser was both a man and a law enforcement officer who was trusted by these defendants and considered a friend,” Tyack wrote. “If detective Rosser was not involved in these situations, these defendants would not have committed the offenses.”

In 2016, bar owner Shantel Williams had run-ins with Rosser while she was employed at Fifth Third Bank on Morse Road, where Rosser worked special duty. In a civil suit, Williams alleged that she was responsible for submitting time cards provided by Columbus police officers working special duty at the branch, but Rosser told officers to only submit through him. She claimed Rosser falsified hours he never worked, so she wouldn’t sign his time sheets. Not long after, Rosser began conducting compliance checks at Williams’ business, Blu’s Lounge Bar on Refugee Road, and later searched the premises, confiscating her personal property, Williams alleged.

The suit claims Rosser then sent two officers to execute an arrest warrant on Williams, who had no prior criminal record. She was taken to jail, but a few months later, charges stemming from the warrant were dismissed. “This is an MO of Rosser – being a bully, using his authority as a police officer to harass and get what he wants,” says David Goldstein, Williams’ current attorney. Williams’ previous attorney was disbarred, and the case was dismissed due to the statute of limitations. (She did not respond to requests for comment through Goldstein.)

Party promoter Brandon “Blast” Adams says he first met Rosser while hosting an event at the Patio, a bar that club veteran Nick Jgenti previously co-owned at the Continent. Adams sent manager Jaquon Johnson to check on a customer about whom he had received complaints. When Johnson returned, he told Adams “to leave it alone because it’s one of the owner’s buddies and he’s a Columbus police officer,” Adams says. “He’s like, ‘That’s Rosser, man. That’s Officer Party.’”

From that point, Adams says Rosser became a regular fixture at events, particularly at Nick’s Cabaret, another club operated by Jgenti, where Rosser would arrive near closing time, drink for free, order shots for girls, then (at some point) retreat with Jgenti to the office, where the pair would sometimes do cocaine together, DJ Adrian Richardson later testified in federal court.

On March 28, 2015, Adams arrived at Nick’s Cabaret for an event headlined by Kansas City, Missouri-based rapper Kstylis. Upon arrival, Adams says he encountered Rosser, drunk and seated with Neil McMeekin, a tall, redheaded man known to Adams as “Handlebars” because of his mustache. McMeekin was one of Rosser’s drinking buddies and briefly served as a confidential informant. (Testifying to a federal grand jury in 2019, McMeekin was asked if Rosser ever sent him out on missions: “No. That would have been cool, though.”) As the party ramped up, Adams talked with attendees, coordinated with members of Highland Security and checked on dancers who were starting to arrive and change into their stage outfits.

When the club emptied near close, a fight erupted in the parking lot, and Adams joined the security team in breaking it up. During the scrum, Adams says he recovered a gun. He brought the weapon inside with the intention of turning it over to Highland Security, which in federal court testimony he described as protocol for recovered contraband. (Attorneys on both sides disputed Adams’ story of acquiring the gun.) Upon reentry to the club, Adams says he was confronted by a staggering, visibly drunk Rosser.

“And then I get punched,” Adams says. “I’m feeling like Chris Tucker in ‘Rush Hour’: Which one of y’all just hit me? And then he was like – boom! – and he hit me again.”

Adams later testified that he raised his arms in the air – the gun in his right hand – and didn’t fight back. Asked on the stand why he didn’t retaliate, Adams replied, “Because I wanted to live. … At the time, police were killing Black guys for less than nothing.”

Following the altercation with Adams, Rosser retreated to Jgenti’s office, where he was discovered by Highland Security’s Brett Waite, who testified that the officer had changed clothes. Waite also testified that Rosser asked him to tell the other members of the security team that the sober officer had entered the club on police-related business, and that Adams pistol-whipped Rosser while he attempted to secure the weapon. After their conversation, Waite testified, Rosser exited to the smoking patio, where he climbed to the top of an outdoor fence and then tumbled over it, later reappearing at the front of the building.

Rosser’s report to Internal Affairs stated he heard from Jgenti that another club owner with a grudge against Rosser had sent Adams to kill the detective. Adams denies these claims, calling them “Wild Turkey out of the bottle.” Charges against Adams were later dismissed.

Adams passed out after being put in a chokehold during the altercation with Rosser, and when he awoke, he says he was handcuffed and lying on his stomach in the middle of the club. He had urinated on himself, and his face was stuck to the floor in congealing blood from a cut near his eye. The only other people in the room were two dancers, who were standing over him, crying, believing him to be dead. When he went outside, there were a handful of police cruisers but no ambulance. “No one is checking on me,” says Adams, who also sustained a broken pinky finger, which never properly set and remains crooked, as well as extensive bruising to his chest. “Why am I handcuffed? What the fuck is going on?” (In Rosser’s federal trial, a jury ultimately rejected the charge that Rosser conspired to violate Adams’ civil rights – a decision U.S. assistant attorney Kevin Kelley attributed in part to Adams’ excitable demeanor on the stand. Rosser’s defense attorney, Robert Krapenc, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Months after the altercation at Nick’s Cabaret, Adams visited Boomerangs, a now-closed bar on the city’s North Side. He ordered a beer from the establishment’s owner, Terry, who returned with a beer and a shot and whispered: “I don’t want you to be mad. This drink is from Rosser. He wants to apologize for what happened.”

Only then did Adams notice the officer, who was seated at a table with two companions, staring at him with “this puppy-dog-looking face.” Infuriated, Adams threw the shot glass on the floor, climbed atop the bar and demanded the DJ play the NWA song “Fuck Tha Police,” which they did. “So I’m up there telling everybody to say hi to the police officer who beat my ass half to death and got me arrested,” Adams says. “And they gathered their shit and got out of there. Then Terry was like, ‘You handled that better than I thought you would.’”

Though Rosser made plenty of enemies during his time with vice, he also had friends. “He was like the titty bar cop, everybody’s buddy,” a former house mom at a strip club testified at Rosser’s trial. And for all his personal failings, Rosser was ambitious and (at times) savvy. He knew the playbook for shutting down problematic establishments and used it often: file a misdemeanor charge, pursue nuisance abatement action and then challenge the renewal of a liquor permit. “Rosser was known as a hard worker who made a lot of cases,” Kelley says. “There were plenty of people who viewed him as a go-getter.”

Jeremy Sokol is one of those admirers. Early in his career, as a bouncer at Sirens, Sokol was dubbed “The Bishop,” a nickname he says was given to him by a manager who noticed the chunky rings that covered his fight-scarred knuckles, drawing kiss-the-ring comparisons to Catholic clergy. In December 2003, Sokol appeared on the cover of Night Dreams, an adult industry magazine, dressed in alligator-skin shoes and a bright red suit, his hands adorned with gold rings, two blondes latched onto him from either side. Above him, the headline read: “The Bishop: Your man for premier VIP service.”

A barrel-chested man with arms like anacondas, Sokol says he got to know Rosser in October 2017 while working as the VIP host at former Northwest Side strip club Kahoots, bonding over their shared history as Marines. As a single father raising a young girl, Sokol was beginning to look for an escape from his life in the skin business. Early on, he was the dad with the colorful suits and shiny shoes. But when his daughter turned 16, it became, “My dad’s at the fucking strip club,” Sokol says. “It’s bad enough we live in a shitty little apartment and all your friends are driving BMWs to school. I need to humiliate you further?”

Rosser offered him an out, promising to help him get a job with CPD in return for the information he believed Sokol could provide as a strip club insider of nearly two decades. Rosser’s offer was similar to one he extended to Brett Waite, formerly of strip club security firm Highland Security. (Furbee, the CPD legal adviser, says Rosser lacked the authority to deliver on either promise.)

In August 2017, Rosser began investigating Kahoots, looking into allegations that a dancer at the club was “offering anal sex for hire,” Rosser said in a deposition. In September and October of that year, Rosser and his vice partner, Whitney Lancaster, frequented the club, receiving lap dances while undercover and writing offense tickets. In court testimony, Kahoots owner Joe Sullo claimed Rosser told him that general manager Joe Vaillancourt had to go, and that if he didn’t fire the manager and reinstate Sokol, who had been terminated weeks earlier, Rosser would “close the club down and file several charges.” (Rosser denied saying this.)

Sullo initially resisted, arguing that Vaillancourt was the best strip club manager in the city. In November 2017, Rosser filed 13 criminal charges against entertainers at Kahoots, claiming in his deposition that the timing was a coincidence. Aside from the three charges filed at Sirens in the July 2018 Daniels bust, every complaint alleging nude or semi-nude dancers touching patrons filed by Columbus police vice detectives between September 2017 and July 2018 was against Kahoots, a total of 38 cases, according to Columbus Dispatch reporting. Sullo, who also owns businesses on the East Coast, told attorney David Goldstein, “We don’t get shaken down in New York City like we did in Columbus.” (Sullo declined to be interviewed.)

Carla Hoover, a former Kahoots dancer, says Rosser filed one complaint against her after she got into a fight with his “best new buddy, Jeremy.” She also says Rosser issued a second citation for a day when she wasn’t at the club. When her attorney filed a petition to have that charge dismissed, she says a different citation was issued for the same date, but this time from Lancaster. In April 2019, Hoover joined five other former Kahoots dancers in a lawsuit against Rosser and Lancaster, alleging the six had been unjustly targeted by the officers. The city settled the lawsuit in February 2020, agreeing to pay the women a total of $185,000.

Sullo, bowing to vice’s pressure, rehired Sokol in December 2017 and terminated Vaillancourt. “I was trying to save our business,” Sullo testified, “and I felt the only way Rosser was going to leave us alone is if I hired Jeremy Sokol back.” With Sokol again in place, Rosser continued with a plan to build a registry of strip club dancers, for which he required clubs to conduct background checks on entertainers as a means of weeding out those with red flags, such as drug arrests and solicitation charges. Sokol says the idea was to build toward a statewide program where dancers would have to submit to a background check and pay a fee to receive a license. “And if you’re on probation in another state, if you have convictions for prostitution or drugs, you’re not working in Columbus,” Sokol says. “That was Rosser’s goal.”

After Rosser was relieved of duty in fall 2018, Sokol’s name became toxic in Columbus strip clubs. He says that Sullo wanted him gone, believing the business was on the decline because patrons knew he had worked with the police. In 2019, Sullo sold Kahoots to apartment developer Preferred Living. “It seems like Rosser was invincible with the city. He was doing whatever he wanted, and I didn’t know any way to stop this,” Sullo testified. “I had no choice but to sell the building.”

Sokol’s dreams of landing a job with CPD also shattered, leaving him adrift for months. Later, when Sokol met with the FBI, he says an agent told him he had been used by the city’s police department, and that he was going to be OK. “It’s the first time I got sleep in two years,” he says. And yet, Sokol’s loyalty to the vice officers remains undimmed, his ire reserved for police leadership and the city attorney’s office. “That guy, you want him out there hunting,” he says of Rosser. “The shit that you are afraid of, that guy’s not.”

On April 19, 2018, club veteran Nick Jgenti went to the funeral of Todd Lancaster, the murdered younger brother of Columbus vice officer Whitney Lancaster, Rosser’s partner. Jgenti, who managed North Side strip club the Doll House at the time, told his girlfriend, Allie Mills, to bartend at the Doll House instead of attending, even though Mills says she was better friends with Todd. Later that night, Jgenti returned to the club with Lancaster and Rosser, both of whom were known to drink at the Doll House in plainclothes.

Mills had known Rosser for years at that point, first running into him at Northwest Columbus strip joint Vanity, where Jgenti worked as a manager and she tended bar. She recalls Rosser walking in wearing hunting gear and a hat. He pursued Mills while she sat at the bar, trying in vain to convince her to accompany him to the strip club next door, Columbus Gold. Mills ran into Rosser again at the Patio, a bar she and Jgenti previously co-owned at the Continent. This time, Rosser had his hair slicked back and spoke with a bad Russian accent. “He sucked at being undercover,” Mills says in a recent interview.

Over the years, Jgenti and Rosser became close friends, hanging out and drinking after hours at the strip clubs Jgenti managed. Mills never saw Rosser issue citations at Nick’s Cabaret or the Doll House. The night of the funeral, Mills later testified, Jgenti gave her a bag of cocaine and told her to go into the Doll House office and use it with Armen Stepanian, a co-owner of the strip club with his ex-wife, Yelena Nersesian, who inherited the club from her deceased brother, Alex Nersesian, a Russian immigrant who operated a drug ring out of the Doll House in the 1990s.

The bag of cocaine was odd for a couple of reasons. For one, Jgenti didn’t normally let her hang out in the office, much less do cocaine there. And Stepanian wasn’t a regular cocaine user. But it also wasn’t entirely unexpected. Mills testified that Jgenti and Yelena had been trying to oust Stepanian, but he wouldn’t sell his ownership share. She even testified that she overheard Jgenti joking about killing Stepanian. He wasn’t joking, though, when he began plotting ways to set up Stepanian. And so she wondered: Is the bag of cocaine part of the plan? Is this the setup?

Help support Matter News in this kind of work by clicking here to make a one-time donation or to sign up as a monthly member.

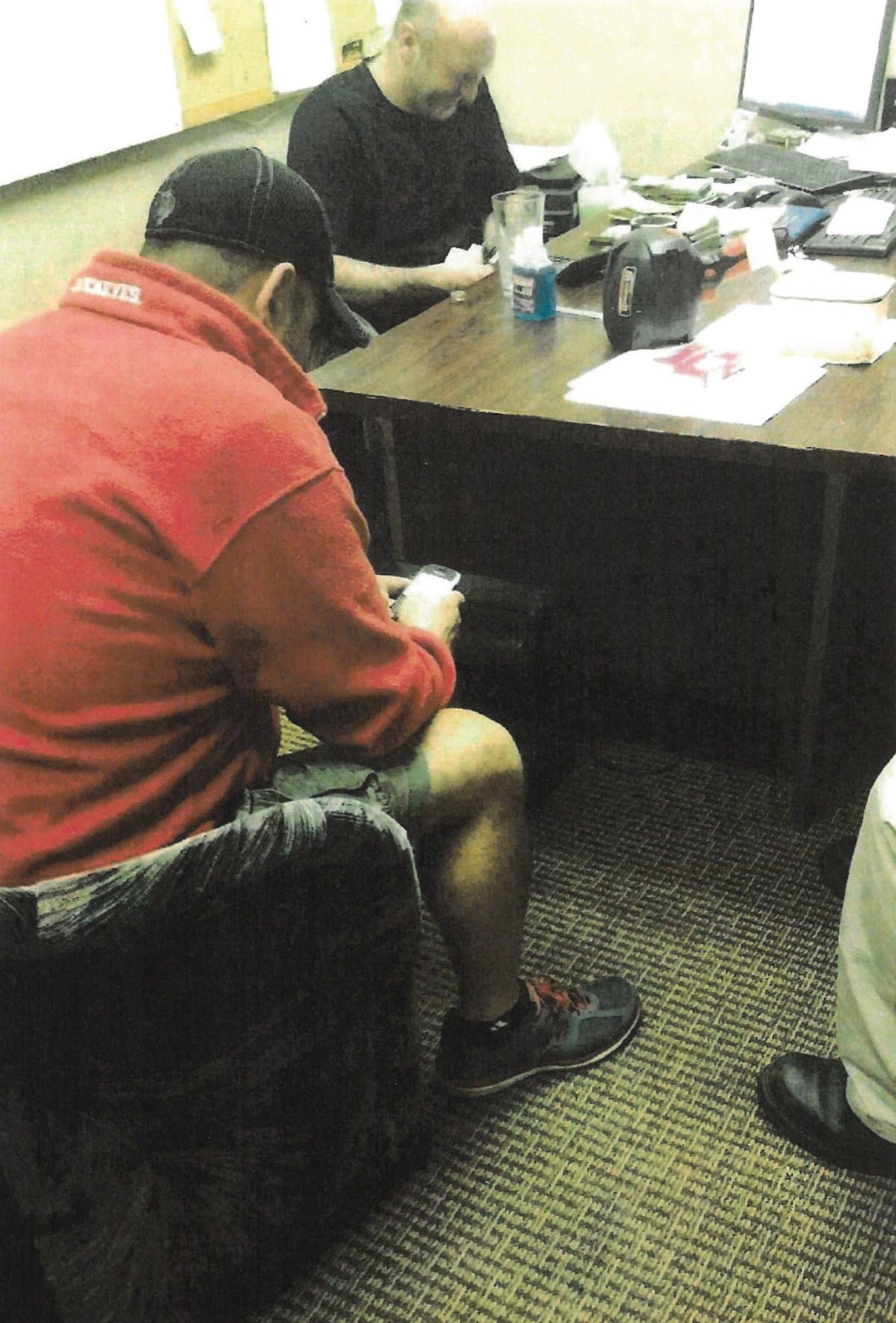

Around 4 a.m., Mills went into the office and did lines of coke on the table with Stepanian, and Jgenti made an unusually hasty exit to the bathroom. Mills sat in the office and listened to Stepanian talk about his relationship problems. Then someone started pounding on the door. Mills panicked and stuffed the bag of cocaine in the pocket of her Lululemon leggings. She opened the door to find Rosser, a badge around his neck, standing alongside some police officers she didn’t recognize. Rosser winked at her and asked, “Where is he?” She told him Stepanian was in the office.

Mills stood in the hallway near the bar area with the few remaining Doll House workers – a dancer, a bartender, a security guard they called Mexican Mike – where they made conversation with police officers, who’d been waiting for Rosser’s signal in a nearby parking lot since 3 a.m. As the patrol officers crowded the area near the office, someone hollered to check underneath a food container. Rosser lifted it up, found some white powder residue on the table and escorted Stepanian out of the office in handcuffs. Outside, he also searched Stepanian’s car.

In the end, despite Rosser’s report referencing a “pile” of cocaine, he arrested Stepanian for possession of a minuscule 0.017 grams of cocaine. Afterward, he interviewed Mills – the only witness he questioned – and exchanged pleasantries instead of asking her about the drugs. The whole time Mills sat there, the bag of coke bulged in her pocket. Afterward, Jgenti told Mills that “Rosser said that he wished that I would have just left the bag of cocaine there so that, I guess, they had more to bust Armen on,” Mills testified. Rosser littered his report of the night with inconsistencies, indicating he initiated the Doll House investigation because he suspected the club was serving alcohol after 2:30 a.m.

Mills felt guilty about the whole ordeal. Five months later, she texted Stepanian. “That night you got arrested at the club – Nick set that up,” she wrote. “Nick was told to bring you down. I just thought you should know.”

In Rosser’s federal trial, Mills served as the star witness for federal prosecutors Kelley and Noah Litton. Her testimony about the Doll House incident was crucial to the one charge that has stuck to Rosser – the only conviction, and the only reason he’s in a federal prison in Estill, South Carolina, until February 2024. The jury found Rosser guilty of conspiracy to violate Stepanian’s civil rights.

Mills had to bear her soul on the witness stand, Kelley says, revealing painful details about her violent, volatile relationship with Jgenti. “She was really persuasive,” he says. “From the jury’s verdict, I would say she’s the one witness they clearly believed all the way.”

When former police chief Thomas Quinlan took over for Jacobs, he asked then-deputy chief Jennifer Knight to come up with a better model to replace vice. Eventually, the division launched Police and Community Together, or PACT, which now falls under the newly formed Nuisance Section reorganized by current police chief Elaine Bryant, who took over the division in 2021.

Alongside PACT in the Nuisance Section are teams like the Abatement Unit, Human Trafficking Task Force, FBI Task Force and the Exploited Children’s Unit. Sgt. Steve Oboczky is PACT’s supervisor and has been with the unit since it formed. According to Columbus police public information officer Melanie Amato, the unit is currently in a rebuilding phase after going dormant from August 2022 until March 2023 while permanent job descriptions were negotiated with the police union and the city.

From the get-go, Knight knew the new unit would need to be heavily supervised, whereas vice officers like Mitchell, Rosser and Lancaster often worked solo or with one other detective. “The PACT Unit is required to have supervision with them while conducting any covert police work. The sergeant is in the field and directly supervising the missions daily,” Amato says in an email. “Any covert work is also monitored by several backup officers.”

Knight, whose time overseeing PACT ended in 2021, also says she intended for officers to rotate in and out of the unit. “We would not have officers that were there 20 years,” says Knight, who retired in January. “I think sunset dates on those types of positions protect everyone.”

Amato says PACT began with 60-day temporary assignments, but it proved “problematic for Sgt. Oboczky to train an entire new team every two months.” PACT moved to six-month assignments, but that created issues with “felony case management, training and team consistency.” Now, PACT has three full-time detectives and a planned fourth, plus a mix of six-month and 60-day temps to round out a team of seven to 10 officers.

The Nuisance Abatement Group, which remains a collaboration with the city prosecutor’s office, Columbus police detectives, Ohio Investigative Unit and other entities, still monitors strip clubs and after-hours joints, but with a renewed focus on violent crime. For instance, in February, Klein filed a lawsuit calling for a preliminary injunction against the owners of the Doll House after a rash of crimes in and around the club, including multiple shootings. Earlier, in December, the city objected to the renewal of the Doll House’s liquor permit. The club is currently closed for renovations as the owners await a hearing this summer.

Street-level prostitution is also an area where the city attorney’s office says community members want enforcement. “Vice wasn’t addressing that effectively because they were spending time in strip clubs,” Furbee says. But after the fall of vice, enforcement of solicitation had to look different. Prostitution is better understood in the context of human trafficking, and, as such, it requires a level of compassion and care for those caught in the cycle of abusive, addiction-driven sex work. “Our goal was, from the first point of contact, the officers treated them with respect,” Knight says.

Knight also wanted to increase penalties for the buyers, often called johns, who paid an average of $74 in fines when caught. “It was always easy to look at the woman or the man walking the street. It’s a very visible sign of a crime,” Knight says. “But we had to start focusing our attention on the buyers.” In the fall of 2021, Columbus City Council passed legislation to increase the minimum fine for sexual exploitation to $300, with rising penalties and the threat of jail time for repeat offenders.

Amato says prostitution arrests are made by uniformed PACT officers in marked cruisers. “PACT also has a policy to not trap or block women in their vehicles. If an individual wants out of the vehicle, they let them out,” she says.

While PACT appears to look and function differently from vice, the division’s recent implementation of a Gang Enforcement Unit seemed to some like a step backward when it comes to specialized units, particularly in light of the Memphis Police Department SCORPION unit, which was formed to target violent crime but adopted tactics that critics called heavy-handed and even unconstitutional. Memphis PD disbanded the unit in late January, just weeks after five of its officers were caught on video viciously beating Tyre Nichols to death.

“I have a lot of concerns about that specialized gang unit,” Knight says. “I think a lot of the problem in creating a gang unit is some of the things that we may have done wrong with vice.”

The new gang unit, a pilot program that has been targeting violent crime since October, also brings back memories of previous Columbus squads that residents derisively nicknamed the “jump-out boys.” But Columbus police leaders say the gang unit isn’t a rogue team. “This unit is different than the ‘jump-out boys’ because they have oversight, they are in uniform, will be in marked vehicles and wear body-worn cameras,” Amato says.

In May 2019, the CPD Internal Affairs Bureau completed a damning report on the Stormy Daniels raid, describing it as rushed, loosely arranged and without a clear objective or well-defined plan. “The investigation demonstrates that this arrest was the culmination of a systematic failure, rather than a singular event,” deputy chief Tim Becker stated in an IAB report given to former Columbus police chief Quinlan.

In testimonials gathered by investigators, officers offered a wide array of reasons as to why they were at Sirens. Sgt. Scott Soha said the detectives were there conducting a random compliance check. Officer Shana Keckley stated the goal was to look for evidence of prostitution and human trafficking. Lancaster painted it as a routine check on a long-term investigation. While Rosser cited human trafficking, and specifically a woman named Pearl, as a focus of the investigation, he neglected to inform any other officers present that night about her, and he couldn’t cite any prior human trafficking complaints made against Sirens. However, Sokol, the strip club veteran, says Rosser sent him a May 2018 email asking the then-Kahoots employee if he knew of two women working at the club, one of whom danced under the stage name Pearl, thought to be a 16-year-old who entered the country from Ireland. “Pearl was real,” says Sokol, who shared screenshots of the email with the writers of this story.

After 19 years with CPD, Rosser was fired in January 2020, along with Lancaster, a 32-year veteran, over their handling of the Daniels raid. Lancaster was also federally indicted with Rosser but acquitted at trial. (He did not respond to an interview request.)

Daniels claimed in a civil lawsuit, which she settled with the city for $450,000, that her arrest was the result of a “political vendetta.” The litigation revealed that Rosser maintained an alternate Facebook page under the name Stevo Shaboykins, where he regularly posted pro-Trump content. Others speculated the arrest could have been business related. Sokol says a rival club had a deal in place with Daniels prior to Sirens swooping in with a higher bid, while a source in law enforcement says the two clubs had engaged in a bidding war for Daniels’ services.

Whatever the reason, the Daniels affair shined a spotlight on pernicious misconduct within the vice unit, inspiring city and police officials to finally act. “Stormy Daniels, I’ll be honest, made it easy,” Furbee says. “This case highlights everything that is wrong with vice.”

This story is a collaboration between Columbus Monthly and Matter News. A shorter version can be found in the June issue of Columbus Monthly.