Mona Gazala takes control of the story

The artist’s new exhibit explores ideas of authorship and debuts in her recently opened space, Gazala Projects, which she intends as a place of freedom for Palestinian creators and archivists.

The first exhibit at Gazala Projects, “Palestine Through the Lens,” doubles as a tribute to artist and curator Mona Gazala’s mother, Salwa, who died in November.

While Mona said that her personality differed greatly from that of her mom – “She was a very passive person who liked keeping peace in the family and I’m more of the troublemaker,” Mona said – the artist did inherit a number of traits from the elder, including a passion for documentation.

“She was always the one who kept the family photographs, and she would sit us down at any available moment and tell us about the stories behind them,” Mona said by phone in early December. “Even in her declining years, when her eyesight failed her, we could still tell her what photograph was in front of us, and she would describe the photograph and the moment it was taken, because it was still so clear in her mind. It was like she kept a record of all of this in her head.”

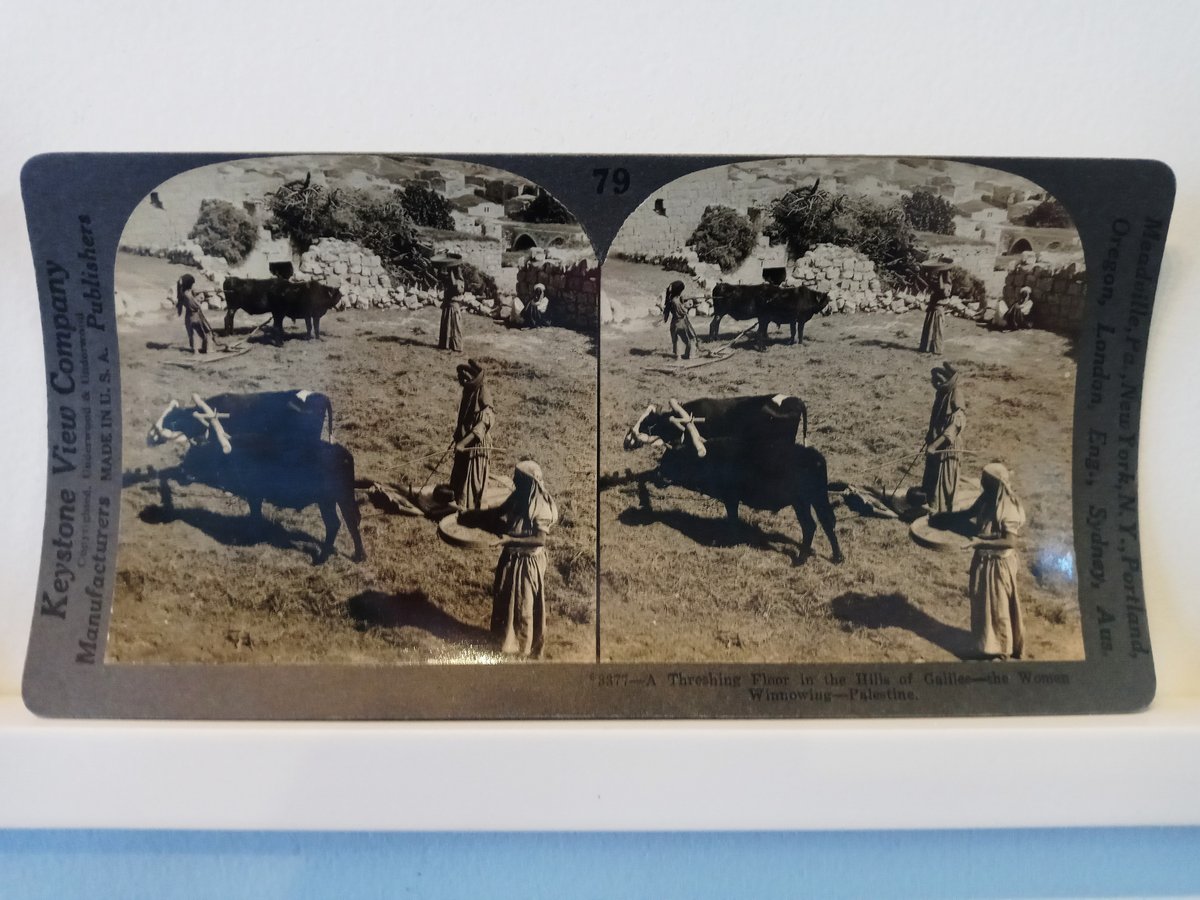

The recently opened archival exhibit, “Palestine Through the Lens” – the first at the artist’s new space, Gazala Projects, located 90 minutes west of Columbus in Gettysburg, Ohio – shares a similar urge for documentation. In the exhibit, stereoscope photographs of Palestine taken by the U.S.-based Keystone View Company circa 1900 are presented alongside modern photos taken by the Palestinian people. The collective picture that emerges is complex, raising questions about perspective, authorship and cultural erasure – ideas that have long been a part of Mona’s practice.

“The subject matter in both sets of photos is scenic and cultural,” said the artist, who sourced modern photos from Palestinian-run Instagram accounts. “But my intention is to invite the comparative study of those photos to raise questions about authorship and how the person telling the story makes a difference. … Whoever tells the story has the power, right?”

The pictures taken by the American company, for instance, present one narrative, capturing what Mona described as “a biblical view of the Holy Land,” largely erasing modern details such as horse-drawn carriages and telegraph poles.

“The images are of people leading mules or camels, or posed in traditional costume, and they appear to purposely be leaving out people who were living in contemporary residences or wearing contemporary clothes, which, of course, was also a part of the reality,” said Mona, who described the Keystone images as both “beautiful” and “an important resource” while also allowing that the modern Palestinian Instagram accounts present a more fully rounded view of the people and culture. “And that gets to the heart of what I want people to compare and contrast about Palestinian stories told by Westerners and stories about Palestinians being told by Palestinians.”

Part of what Mona hopes to accomplish with Gazala Projects – housed in a building the Columbus expat purchased early in 2022 – is to create a space where Palestinian artists can present art unencumbered and absent censorship. Beginning in 2023, the plan is to feature one archival exhibit and “two to three” exhibits from visiting artists each year, starting with Albuquerque-based printmaker and animation artist Ameerah Badr, who will display in the gallery in March.

“I’ve been working pretty intensely on art and research projects focused on my Palestinian identity, and that has caused me to experience some pretty stressful situations in galleries and academia, including but not limited to censorship and being asked to tone the work down,” said Mona, whose self-described “troublemaker” urges continue to reveal themselves in her unending push to shake up cultural institutions and prevailing attitudes while advocating for greater equality and social justice. “And because of this, I envisioned having a space where freedom of expression for Palestinian artists and archivists was the default setting and not the exception.”

Gazala Projects has also helped ground the artist in other ways. For years, Mona has wrestled with the meaning of the word “home,” telling Alive in 2021 that “the idea of home is a really complicated question for me.”

“Obviously I can never go back to the place my parents came from … so [archiving these materials] gives it some shape and form for me,” she said of her practice at the time. “It gives it some sense of reality. I can never feel that soil under my feet. I can’t physically touch anything there. This is my only real connection.”

More recently, however, Mona said a new understanding of that idea has awakened inside of her, one which she traced to a number of life-altering changes she has undertaken, in particular leaving Columbus for the rural environs of Gettysburg to launch Gazala Projects this past summer.

“You always hear children of immigrants saying that they have a hard time figuring out where they belong, and I would be among those people,” she said. “I’m incredibly happy to be here right now. But at the same time, after making a couple of major moves in my life over the last several years, I’ve become kind of comfortable with the idea that there isn’t necessarily one place where I belong.”