How to breathe in a crisis

‘The drug war never stands still,’ journalist and activist Garth Mullins said on the Crackdown podcast, ‘just when you think you’ve figured things out, the ground underneath you starts to shift.’

The first time I saw Rayce, he was sprinting.

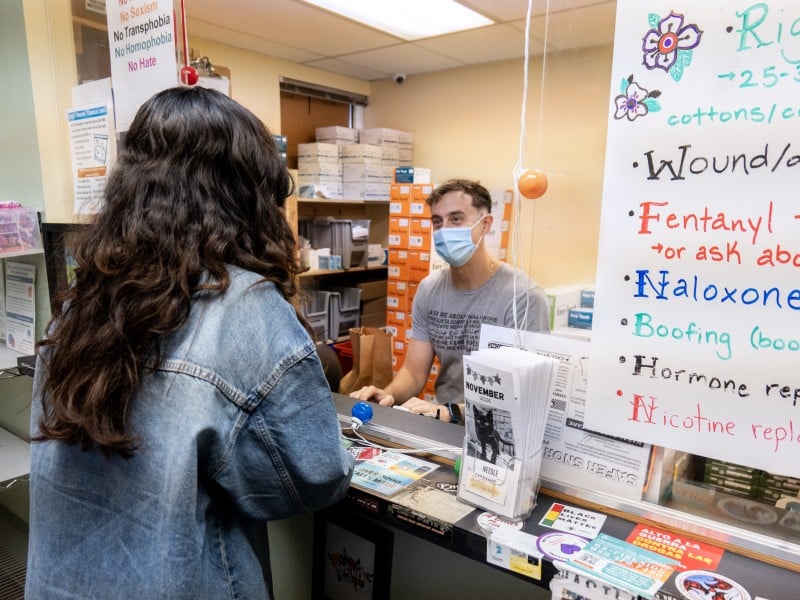

I was part of a group touring OnPoint NYC’s overdose prevention center in East Harlem. It was a busy August morning, and we were waiting in the lobby, a hive of positive energy, about to visit the safe consumption space when he sped by us – long hair up in a bun, a quick wave, and a portable oxygen tank trailing behind.

My group was then ushered into the safe consumption space proper where, in the shadow of a sign that reads, “This site saves lives,” people can use illicit drugs under the watchful eye of trained staff. Since Nov. 3, 2021, OnPoint staff in Washington Heights and East Harlem have intervened in over 819 overdoses.

Indeed, the safe consumption space is built to save lives: naloxone, safe-use supplies, and oxygen are at the ready. And skilled staff – one is a phlebotomist, another a trained EMT – monitor the participants. Staffers can also track what is currently in the drug supply. For example, there had been four overdoses with a particular bag the day before my visit, so staff were able to warn participants who brought in the same bag.

OnPoint is more than a safe-use space. There’s a medical clinic where people can get care without stigma, a laundry room, showers, three meals a day, social workers, an outdoor garden, and more. But what most stood out to me on my visit was a vision of love and respect for the dignity of every human life; it seemed to shimmer throughout this space.

Minutes later, we were introduced to Rayce Samuelson, an overdose prevention specialist, who had only just passed us in the lobby. He told us that someone had alerted staff of a possible overdose on the street, so he had grabbed his “to-go overdose box and oxygen tank” and ran outside.

“Are you okay?” someone in our group asked.

“Yes, thank you,” Rayce replied. “I’ve done it over 100 times now. I feel really confident.”

Rayce did seem confident. He appeared serenely calm with a brilliant smile despite, or because of, what had just happened: He’d just saved a life. He seemed the kind of person you’d want to be around during a crisis – someone who always remembers to breathe.

“I didn’t have to use any Narcan,” Rayce said. “Just put him on some oxygen, grabbed a wheelchair, brought him in. Now he’s just hanging out with my other staff.”

I was struck by the fact that he’d only used oxygen. Rayce told us that 80 percent of their reversals in the overdose prevention space are just with oxygen.

As xylazine and other adulterants enter the illicit drug supply, some overdose victims aren’t responding to naloxone alone. Because of this, some public health and harm reduction advocates are reminding people who use drugs and their allies that rescue breathing can also be an important intervention. Rescue breathing is not the same as having a tank of oxygen on hand, as they do at OnPoint and other safe consumption spaces. One simple mantra: Tilt neck, pinch nose, breathe into mouth, count to 5, repeat.

Folks who are going to be in a place where they might be administering rescue breaths should get CPR/first aid certified to make sure they’re doing it properly. But there are a number of online resources (Red Cross, Next Distro) that can help get you started.

It takes practice. And it takes, perhaps, a special kind of skill: The ability to breathe and remain calm in a stressful situation.

I spoke with Rayce again the other day, and he told me that, for his part, he can stay calm during an overdose emergency because of his training, his ability to trust the process, and the knowledge that he has a well-trained staff. He’s also experienced.

“I reversed my first overdose when I was 16,” Rayce said. He didn’t have naloxone, but he called 911, and they instructed him to do CPR.

Just before I spoke with him, he said, he reversed three overdoses in about 10 minutes.

Rayce said that it can be hard to deal with the intensity of this work, but that he and his coworkers take steps to address mental health. In fact, the organization prioritizes it, encouraging folks to take mental health days. If there’s a particularly hard overdose, they’ll shut down to debrief.

That’s a good thing, and maybe something more folks should be doing. Working in harm reduction during this overdose crisis, it can become your whole world. And it’s a harsh world right now. Just writing about this crisis, confronting rambling politicians who are gearing up for a renewed war on drugs, and states pushing policies that will only exacerbate the pain, can feel overwhelming.

Like an arrow at full draw, I’m holding my breath in tense anticipation, waiting for things to get better.

“The drug war never stands still,” journalist and activist Garth Mullins recently noted on the Crackdown podcast, “just when you think you’ve figured things out, the ground underneath you starts to shift.”

As I’m writing, a notification pops up on my phone, a “Deadly Batch Alert” from Columbus-based SOAR Initiative. Such notifications pop up often, with warnings of fentanyl being sold as Xanax, cocaine or meth with fentanyl, or of multiple recent overdoses or overdose deaths.

They are reminders of the need to breathe, and of our ability to breathe for those who can’t.