Jackie Lewis honors memory of late son Shaun in push for openness

One Ohio Recovery Foundation is tasked with distributing a majority of the money awarded to the state in opioid settlements but has been resistant to public comments from those with lived experience.

The night before Shaun Lewis died from an overdose, his 96-year-old grandmother’s feet were hurting so bad that she started to cry. Shaun asked her to sit down in a kitchen chair while he got a box of Epsom salts and a tub filled with warm water. He gently placed her feet in the water and massaged them, talking calmly to her for more than an hour.

Shaun’s mom, Jackie Lewis, watched him work while she washed the dishes. He was so gentle, she said. When he was finished, he dried her feet, rubbed them with lotion and sat with her and talked. She has dementia, but Shaun gave her space, let her speak, engaged with her.

“And then he was gone the next morning,” Jackie said. “But that was my son. He was like that.”

It’s not hard for Jackie to recall stories that illustrate her son’s empathy for others. He was organized and made a list every morning of what he had to do that day. And each day the list would include “Take care of my family.” Jackie has a series of photos of him on a wall in her home. In the first, Shaun crouches down, reaching into a bush. In the second, he pulls out his hand, which holds a small house sparrow. In the third, the bird is on his shoulder, and he’s feeding it.

Jackie said that Shaun was always running towards people who were hurting and needed help. In his short life, by his count, he reversed more than 20 overdoses.

“He always wanted to help people and animals that were broken in spirit because he was broken in spirit,” she said. “And he knew how they felt.”

That’s how on the eve of his death last October – darkness hovering around the windows, street lights clicking on – Shaun Lewis came to massage his grandmother’s feet. Now Jackie is caring for the elder and raising Shaun’s 7-year-old daughter, who also lost her mother to an overdose. The days are long, the needs are endless. She’s used up her retirement savings and feels fortunate to have supportive family members nearby. But she still struggles.

Of course, there are many Jackie Lewis’ – people grieving while raising grandchildren or supporting someone with substance-use disorder. There are frontline harm reduction workers, grassroots organizers, and lots of other people living in pain. And all of these people could use some support.

Ohio has been awarded $1 billion from settlements with opioid distributors and manufacturers. A majority of that money – 55 percent – will be doled out by the One Ohio Recovery Foundation, a nonprofit created by the state to do this work. The foundation is governed by a 29-person board composed mostly of political appointees and only one Black person. (In a state with a disproportionate number of overdoses among Black people, this is problematic.)

How the money from the settlements gets distributed should be as clear and open as a new day. But the foundation’s board hasn’t been as clear nor as open as it should be – this is a national trend – and was sued last August by advocacy organization Harm Reduction Ohio, which claimed that the board was operating mostly in secret and not following the state’s open meetings and open records laws. One Ohio argued it was a private foundation and did not have to follow the same rules as public entities.

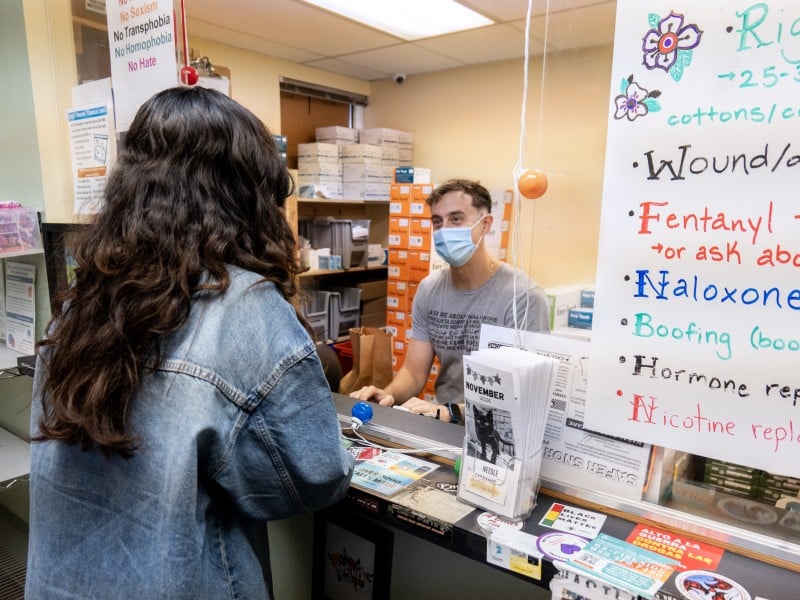

In March, Franklin County Judge Mark Serrott ruled that One Ohio is, in fact, a “public body” and should thus be as open and transparent as any state entity in adhering to the Ohio Open Meetings Act. This transparency could include letting the victims of this crisis – to whom this money truly belongs – speak on the record and offer their thoughts about how the money should be spent. In reply to an email asking specific questions related to public comments at meetings, One Ohio issued a statement to Matter News asserting that it was currently engaged in “the extensive work necessary to properly establish a brand new organization of this magnitude,” but would “certainly consider inviting Ohioans to present best practices and ideas that can help reduce the scourge of addiction across our state.”

On August 11, 2022, Jackie Lewis attended a One Ohio board meeting with a group organized by Harm Reduction Ohio. It was no small effort on her part; it required arranging someone to watch her mother and granddaughter. But she went because she hoped that she might have an opportunity to share her experience, despite not having been invited to speak. At the time of this meeting, Shaun was still alive, and Jackie was still fighting for him.

The board had just been sued and so it went unceremoniously into executive session. Jackie didn’t get to speak to anyone. She has paid attention to the meetings via livestream since then, but she finds them frustrating. There’s no space for people with lived experience to speak, she said.

I get it; this is a huge undertaking. But people are dying and affected communities need help now, so why not solicit it from people who have already been in the trenches for decades? Optics matter. In Rhode Island, opioid settlement money has already been allocated to support overdose prevention centers. New York had a call out for folks seeking funds that will support street outreach (it closed yesterday). Kansas has an RFP due next Friday. And there are more opportunities in the works in other states.

Earlier this year, One Ohio announced it is forming an “Expert Panel” to help guide decision making. Jackie applied, but she’s not hopeful of her chances. She said she felt the application was biased, asking about degrees, publications, public speaking engagements, professional recognition and so on. There’s a box for folks to talk about their lived experience, but it’s limited to 300 words. (A fraction of what I’ve managed to write here, which contains a mere outline of Jackie’s lived experience.)

But Jackie’s not giving up hope. When she is allowed to speak, she’ll advocate for help with kinship care, free treatment, and support for workplace education around substance use disorder.

A spokesperson from the board offered to work directly with Jackie to set up a meeting with “leadership.” I hope they will follow through with that offer. But, to be clear, private meetings are different from public ones. The One Ohio Foundation Board meetings should have a space for public comment. It is the most democratic thing to do. The board even discussed the possibility during the meeting on June 23. Some members were in favor, but with time limits, and at least one member opposed the idea altogether. They could again revisit the idea at the next meeting, currently set for May 10.

Yes, emotions may run high. There may be anger. There may be tears. But this settlement, however flawed it might be, could offer many people who have been affected an opportunity to grieve and to share their stories in a way that will bring more truth to the public record. More importantly, this money gives people an opportunity to effect real change and to help save lives. It’s the least the board could do for people with deep lived experience like Jackie.

Jackie can draw a line from prescription pain medications to Shaun’s substance use disorder. He had scoliosis, and in eighth grade his doctor started him on pain and anti-anxiety medications. He struggled with PTSD, anxiety and depression as a result of past traumas. She said he told her once that he knew when he took those medications all the pain and emotions would go away. During his senior year of high school, the doctor cut Shaun off when they found marijuana in a blood sample. He began using illicit opioids. Without insurance, he struggled to get help, and Jackie said she could never really afford to get him all the care he needed.

Now, she carries so much on her shoulders.

When the day is done, after putting her mom and her granddaughter to sleep, and when all is settled, Jackie said that she typically takes a moment to sit down and cry.

She cries and remembers her son massaging his grandmother’s feet. Her son, cradling the abandoned sparrow, feeding it until it could safely fly away on its own.