A short history of prohibition in Ohio

To know the history of prohibition in our state is to know the devastation of unintended consequences, and the willful way humans carry on without acknowledging their mistakes.

Fred Reynolds collapsed in front of a Cleveland movie theater on an unseasonably cool late July night in 1926. He was rushed to the hospital but died the next morning. His wife was later found at their home in serious condition. She survived, but like her husband had fallen victim to poison liquor. According to United Press reports, the couple purchased the liquor in Buffalo, where 37 deaths had already been traced to the same batch.

The same year, on Christmas Eve, more than 60 people showed up to New York City hospitals, hallucinating, losing their sight. Eventually, 23 people died, the result of drinking poisoned liquor. In total, 400 died in New York City in 1926 from poisoned liquor – a number that nearly doubled the following year. All across the United States, thousands were dying because of prohibition.

There’s a direct line that runs from all those poisonings to Westerville, Ohio, once called the world’s capital of prohibition. The city was home to the Anti-Saloon League, one of the central advocates for the Volstead Act, the law that ushered in the 18th Amendment and more than a decade of the prohibition of alcoholic beverages in the United States – one of the greatest policy failures in U.S. history.

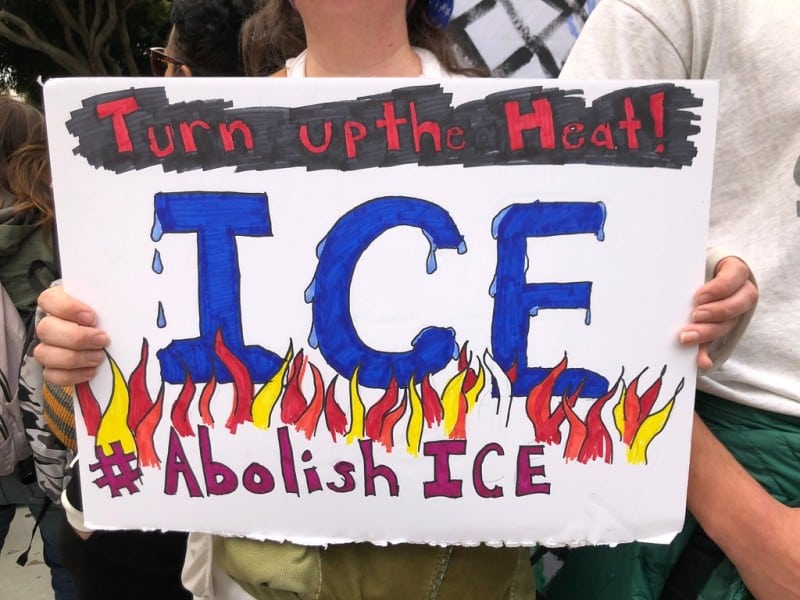

We’re hearing the rumble of prohibition again. Next week, the U.S House of Representatives is expected to vote on the HALT Fentanyl Act, which would make permanent the schedule 1 classification of fentanyl-related substances and impose mandatory minimums for distribution. On April12, the Biden Administration designated xylazine in combination with fentanyl an “emerging threat,” which will lead to increased monitoring of the drug and Drug Enforcement Agency crackdowns. Weeks earlier, Gov. Mike DeWine directed the State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy to classify xylazine as a Schedule 3 controlled substance. Ohio was one of the first states to do so. Once again, we’re the heart of it all in prohibition land.

No doubt that xylazine – a non-opioid sedative and painkiller used by veterinarians – is problematic, leading to potentially prolonged sedation and open wounds. But cracking down on the latest drug doesn’t address an adulterated supply or overdoses involving multiple substances, just like the 18th Amendment didn’t address alcohol use disorder or alcohol poisonings. It will only make it worse.

Before prohibition, beer was the most popular alcoholic beverage in the United States. Almost overnight, people switched to liquor. In Chasing the Scream, Johann Hari writes, “Hard liquor soared from 40 percent of all drinks that were sold to 90 percent.” Tastes didn’t change – laws did – and it’s easier to ship liquor than beer. Just like it’s easier to ship fentanyl than heroin.

But bootleg hard liquor became scarce, and only rich folks could afford what was left. People looked for other sources of alcohol, and much of it was poison. Home stills would distill wood to make methanol, which produces formaldehyde and then formic acid as it breaks down in the body, potentially leading to blindness or death.

Others accessed “denatured” industrial alcohol (like that used for cosmetics or medicine), which manufacturers laced with additives to make it toxic. For years, the Federal government encouraged the practice, offering tax breaks to industrial alcohol manufacturers who tainted their supply – a policy that contributed directly to increased deaths.

Some folks got alcohol legally from their local pharmacies. One of the most popular medicines was called Jamaica Ginger, which went by the nickname “Ginger Jake.” The medicine, 70 percent alcohol, could supposedly help address headaches, promote digestion, and cure colds. But it contained triorthocresyl phosphate, which attacked the nervous system and led to a paralysis commonly called “Jake Leg.” In March 1930, at least 125 people in Cincinnati were diagnosed with it.

Prohibition failed in the past, and it is failing now.

Here’s the most recent history we have before us: Sometime in the 1990s, formulations of opioids entered this state via medical doctors and legitimate pharmacies. Those pills offered powerful relief to people experiencing pain. Some of those pills made their way into the illicit drug supply. And some ended up being sold by pharmacists accepting scripts from cash-only pain clinics. The drugs did their work.

The pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors knew that something was happening, and they let it happen because they stood to gain from it, one pill at a time. Their response should have been, “Hey, we see this thing is happening, and we want to figure out a solution.” That solution should have involved opening methadone clinics, treatment facilities, and funding free and better healthcare.

But in 2011, the pill mills were shuttered, and pharmaceutical grade opioids became less and less accessible. First heroin filled the void, and then fentanyl. And now it is whatever it is. A recently released CDC Report tells the story: “From 2016 through 2021, age-adjusted drug overdose death rates involving fentanyl, methamphetamine, and cocaine increased, while drug overdose death rates involving oxycodone decreased.”

As policies to clamp down on a safe supply of opioids, people shifted to an increasingly dangerous illicit supply, with the impacts felt more heavily by the poor, the marginalized.

On a reporting trip in Vancouver five years ago, a source with many years of working on the frontlines of overdose prevention used the term “genocide” to describe all the deaths she’d witnessed for years in her community. When I winced at her use of the term, she pushed back. The people most affected by the consequences of a poisoned drug supply were poor. They were Black and Brown. They were Indigenous. Those most affected have the least power and are considered the most expendable. What would you call it, she asked?

To know Ohio’s history of prohibition is to know the devastation of unintended consequences, and the willful way humans carry on without acknowledging their mistakes, or their role in making them. Politicians hunting red meat serve up the solutions with greatest and grossest consequences.

If research, lived experiences and historical evidence demonstrate that prohibition has always been a failure, what are we doing? The reality is that politicians want to say they’re taking action, so they are forever chasing the latest problem drug, punching down, pressing their gnarly thumbs down on the people who use them.

Xylazine is here. In recent months, I’ve spoken to folks who have had positive xylazine test strip results. According to a recent report from the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy, there were only 15 xylazine-involved overdose deaths in 2019. In 2022, there were 113. The toll that a drug like xylazine takes on the human body can be awful. The wounds alone are intense.

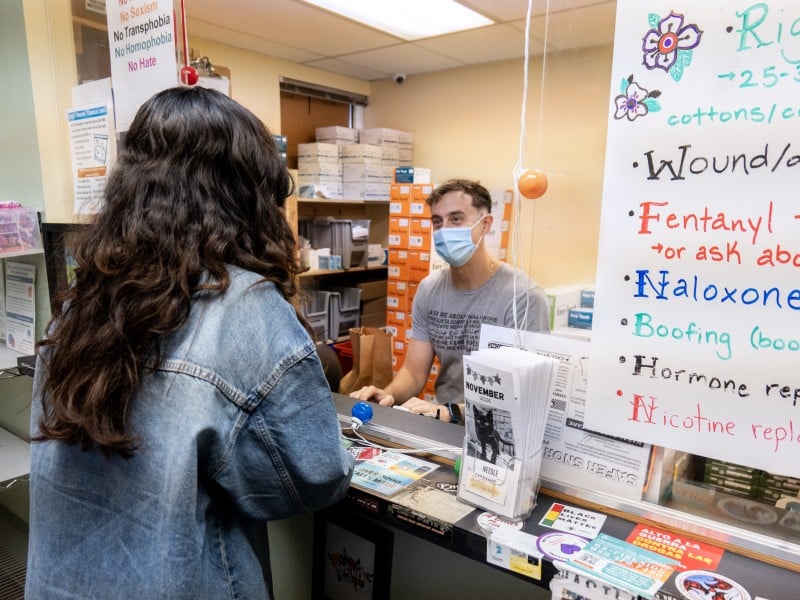

But supply-side solutions only lead to more dangerous substances, and more deadly combinations. Instead, train health professionals how to respond to it. Promote public education and harm reduction. Ramp up easy access to evidence-based treatment like methadone and buprenorphine. Flood the streets with naloxone. Create overdose prevention sites. And increase access to xylazine test strips.

When I started reporting on this crisis, I believed that we would one day see its end. And yet, it now feels as though we are at the beginning of something worse. I hope I’m wrong.