Columbus moves to decenter police in mental health crisis response

Five to 10 years from now, Columbus and Franklin County could have a unified and streamlined crisis response system that looks very different from the one that currently exists.

Chana Wiley has been telling the story of her brother’s beating death by seven Columbus Division of Police (CPD) officers for almost seven years. Now she is telling the story of her 21-year-old son’s non-lethal beating in September by the same police department. Both of her family members suffered from mental illness, and both were in crisis when police officers arrived.

Wiley testified at the Columbus City Council Safety Committee Hearing on Oct. 3, asking how many residents need to be harmed before the city deploys a non-police response to mental health calls.

“We know that the police are trained well to de-escalate. We would just like to do it a different way and be innovative,” she said.

City officials, community program CEOs and area residents testified about the patchwork of crisis response programs and pilots currently in operation. Committee Chair Emmanuel Remy asked each of them what their vision is for the future of crisis response. Council Chair Shannon Hardin asked more direct questions about what they are learning from the current pilots and how quickly the city can move forward toward a non-police alternative response.

The consensus was that five to 10 years from now, Columbus and Franklin County will have a unified and streamlined crisis response system that will look very different from what currently exists. They all agreed it would be a collaborative effort among public departments and private agencies.

Dr. John Draper, an international expert in crisis response who is consulting with the Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Board of Franklin County (ADAMH), predicts that someday his grandchildren will ask him, “Really? Was it true that cops used to come to your door if you were thinking about suicide?”

What is a mental health crisis?

Erika Clark Jones, CEO of ADAMH, explained that anyone in a mental health crisis considers it an emergency, but not all crises are public safety emergencies requiring a police response. Draper believes that who draws that line and where they draw it should be established in national standards that don’t currently exist.

When patients suffer from severe mental illness, their symptoms can range from an inability to take care of their basic needs to paranoid delusions that make them appear to be a threat to themselves or others.

The night that Wiley’s brother, Jaron Thomas, was beaten, he said he was hearing voices and needed to go to the hospital. He called Wiley, who was home with her baby and couldn’t leave. She encouraged him to call 911 for a squad to take him.

In some Columbus neighborhoods, police cruisers accompany medics on calls to “clear the scene” before medics enter the home.

When Thomas saw the flashing lights, he was relieved that someone was there to help, Wiley said. He ran out of his house toward them. The police officers misinterpreted his actions as aggressive and apprehended him, took him to the ground, placed him in handcuffs, and continued beating him until his heart stopped.

Police then moved their cruisers out of the cul-de-sac so medics could get to the house.

How can social workers and other clinicians help?

In his opening remarks at the Safety Committee Hearing, Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther stressed that alternative crisis responses free up police hours for solving crime and responding to public safety calls.

Ginther said he is particularly proud of the Right Response Unit (RRU), a collaborative effort between CPD and Columbus Public Health (CPH) that works 16 hours per day. A social worker is on the line with a 911 dispatcher, working to triage the call in an attempt to de-escalate the situation before the police arrive. The social worker can also connect the caller with resources to resolve the crisis without a police response.

Of the 3,000 calls taken so far in 2023, police did not need to respond to 900 of them, while 350 were referred to the co-responder Mobile Crisis Team (MCT), which has a social worker riding with a police officer. The other 1,750 calls dispatched uniformed officers in cruisers.

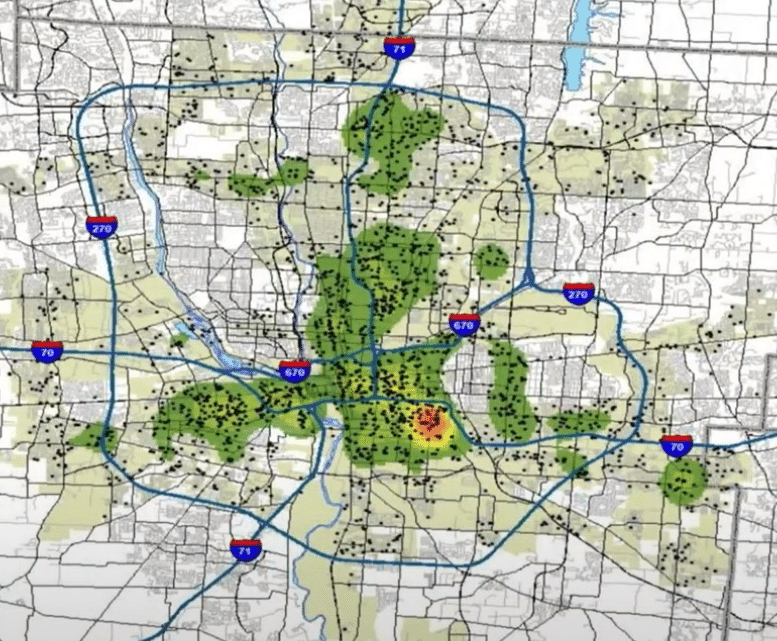

CPD averages 2,000 mental health-related calls per month, according to police. MCT can only handle 15 percent of them at this time.

Steve David, with the Columbus Safety Collective, maintains that police are always the wrong response. “There is plenty of evidence that [police] cause harm when responding to these calls,” David said. “They view everything as a threat. People who are not police officers bring a fundamental shift by going into a home with an attitude of service.”

Social workers have national standards and state licenses to which they are accountable. They have the power to write a “pink slip,” which requires a doctor to evaluate a person within 72 hours. The four criteria they use are homicidal tendencies, suicidal tendencies, a danger to themselves, and not attending to their basic needs.

With all the skills they have to offer, the challenge repeated by each city agency was the lack of supply and the resistance of licensed people to work the hours required of crisis response. Assistant Health Commissioner Anita Clark told the hearing that they would need to do more “pipeline work” to develop a pool of social workers to hire.

Will Columbus try a non-police response?

City Council allocated $1.2 million in the 2023 budget to pilot a non-police response. David is encouraging Hardin to contract with a national expert to install a pilot at CPD. (As of this writing, David said he has not learned if any of that money has been spent.)

Hardin thanked David publicly at the hearing for his advocacy and leadership, and then asked for his opinion on the Netcare Access non-police response program. David said he values that program, but key pieces are missing.

The relationship between Netcare Access and CPD is a sticky one. More than five years ago, the two collaborated on a co-responder model where a social worker from Netcare would ride along with a CPD officer responding to mental health emergencies. That relationship ended due to disagreements on how patients and family members should be treated, with social workers following their professional standards and officers following their division directives and use of force training.

Dr. Brian Stroh, CEO of Netcare, described a new program funded last year by ADAMH in which a social worker and a trained peer supporter would respond to crisis calls coming into the new 988 mental health crisis line, answered locally by North Central Mental Health and Netcare.

Pam, a peer support worker with the Netcare program, has never felt the need to call the police. “When you understand, as a peer, what the patient is experiencing, you don’t fear them,” she said.

David said this is the key to solving the staffing issues the city sees ahead of them. As a social worker, David sees the barriers that minority youth have to enter the profession, and he believes employing community members who already do this work as neighbors, church members, friends and family of folks with mental illness could be the solution.

The Netcare program provides a similar amount of training for peer support workers as police officers receive in the police academy. They are then paired with a social worker in the field. David said this expertise within the community should also be tapped to create an oversight commission. He encouraged the City Council to begin this group soon, empowering it to oversee the rollout of new strategies.

Within the city, non-police response teams also handle calls placed to the Franklin County Youth Psychiatric Crisis Line (614-722-1800), which are answered by licensed social workers at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. The crisis line has a mobile response and stabilization service with four teams that work 9 a.m.-9 p.m. Monday through Friday. The teams include social workers and parent support specialists, with peer support assistants expected to join soon.

Regardless, Clark said even if the city installs a non-police response unit, she would still want the social workers equipped with radios connected to the emergency call center so police could be summoned quickly.

911 vs 988 vs other crisis lines

Jones advocated for ongoing improvement in the crisis care continuum which she breaks down into 1) Someone to call; 2) Someone to come; and 3) Somewhere to go.

Fifty-five years ago, the first call was placed to 911. The emergency line was available to 93 percent of the country in 2000. Today, 98.9 percent of the population has access to emergency responses through the system. But not everyone.

CPD still has a non-emergency line (614-645-4545) that now has an option to select if you want to report a mental health problem or need resources. Those calls are also routed to the Right Response Unit.

Ten years before 911, the first suicide prevention center was established. On July 16, 2022, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline transitioned to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. In Ohio, the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (MHA) ushered in the service with one of the most widespread launches in the country.

The information distributed by MHA promises that most crises can be handled by call, chat or text, but that the service can also dispatch a mobile response team, which may be a behavioral health team or first responder team, either of whom will meet the person at their place of crisis.

In Franklin County, North Central Mental Health answers the calls, with backup from Netcare. The calls that need in-person response are dispatched to the Netcare Mobile Crisis Team. Stroh reported that they receive 150,000 calls per year from 988 and 614-276-CARE. Of these, 87 percent are resolved without the patient needing in-person assistance or transportation. Only 3 percent are referred to 911 call centers.

Jones described a 911/988 workgroup that has been formed to embed 988 responders in the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office and the Grove City Call Center to establish standards for handling calls.

Clark reiterated in her testimony to council that the data collected by all the partners in this effort must be evaluated to find the best practices.

Jones envisions a day when 988 becomes the care traffic control center and “one call will do it all.”

Draper is consulting with ADAMH to navigate the predictable bumps in paving the road to a seamless 988 system. He cautioned that it is in its infancy with a long way to go to be what it can be, and he’s seen challenges arise ranging from consumer awareness to geolocation concerns (can they see where you are calling from?).

What happens after the crisis?

Dr. Robert Lowe, Emergency Medical Director at Columbus Division of Fire, admits that the system currently in place may place an unfair burden on a number of patients by taking them to the most expensive and most time-consuming health care options: emergency departments at local hospitals.

Remy summed up the unsustainable system in this way: “We have a ‘You Call/We Haul’ mentality. We are literally picking up people to take them to an ER to get a prescription filled.”

People who call 911 with a mental health crisis know there is a chance they will be transported to an emergency department and then possibly held for three days for a psychiatric evaluation. As a result, some might be hesitant to call when what they really need is access to care in a city with very long wait times for counseling and psychiatric appointments.

ADAMH expects to finish construction in 2025 on a new Crisis Care Center near downtown Columbus. This will be a walk-in service, not unlike an emergency department, with rooms to let folks stabilize before they return home.

Preventing the next crisis by offering consistent care is the only sustainable plan. The crisis response programs at CPD, Netcare and Children’s Hospital have components of follow-up care, but none are a substitute for a long-term relationship with trusted mental health practitioners.

Wiley’s son was traumatized seven years ago by his uncle’s violent death. His energy and focus continued to decline. Then he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder two years ago. He resisted “pills,” saying it made him feel like an old person. He has been unhoused intermittently since his diagnosis.

The night the police attacked him, Wiley said, he had been trying to gain access to Star House, the only drop-in center for homeless youth (ages 14-24) in Columbus. Wiley said when the facility turned him away for previously breaking the rule against vaping, he threw some rocks against the building.

Star House called the police and officers found him at Burger King several blocks away. He was scared and ran from them. They caught him and arrested him for menacing. Wiley said he had multiple bruises and skin missing from his arms when she eventually got to see him.

Wiley doesn’t know where her son can get care, how he can find housing, or what resources are out there for him. Any option that possibly involves the police would retraumatize him. “I don’t know where to call,” she said.